His Depression-themed, worker-centred art is considered an ‘irreplaceable’ historical record. Hutchinson understood what it meant to be marginalized.

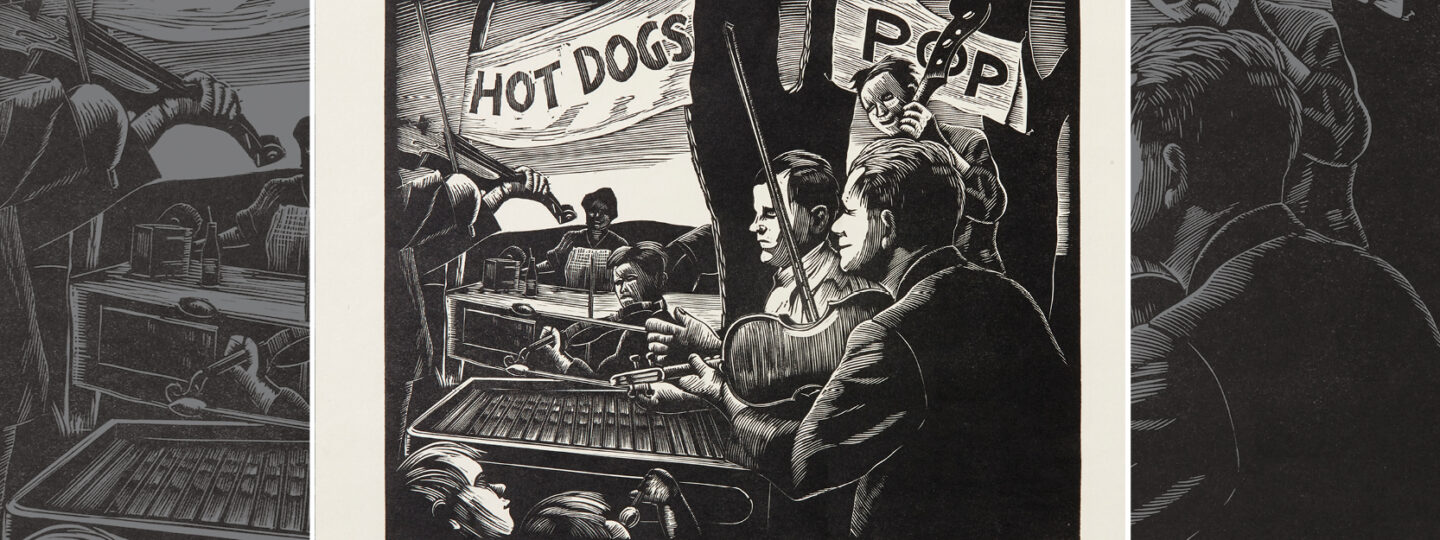

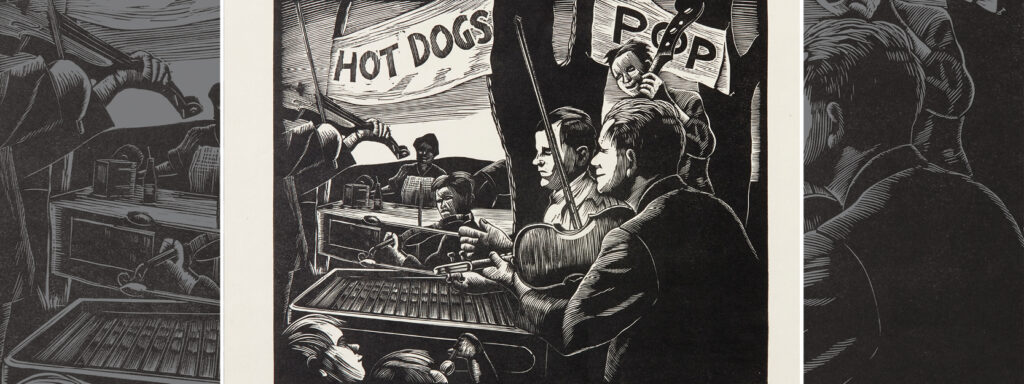

Leonard Hutchinson is best known for evocative 1930s Depression-themed and Japanese-style woodblock prints of working people and places like barns, mills, homes, and landscape in and around Hamilton.

In his lifetime Hutchinson produced 136 such prints and they have been exhibited in art galleries across Canada, including the Art Gallery of Hamilton in 1995.

What draws you to them is their directness and simplicity, minus any rhetorical signage accompanying them, observed the Globe and Mail’s art reviewer John Bentley Mays in 1981, one year after Hutchinson’s death.

Hutchinson also produced drawings, water colour and oil paintings and thousands of photographs, all carrying a similar theme.

Mays called the entire body of Hutchinson’s work “a unique and irreplaceable” historical record of a time period that still haunts us today.

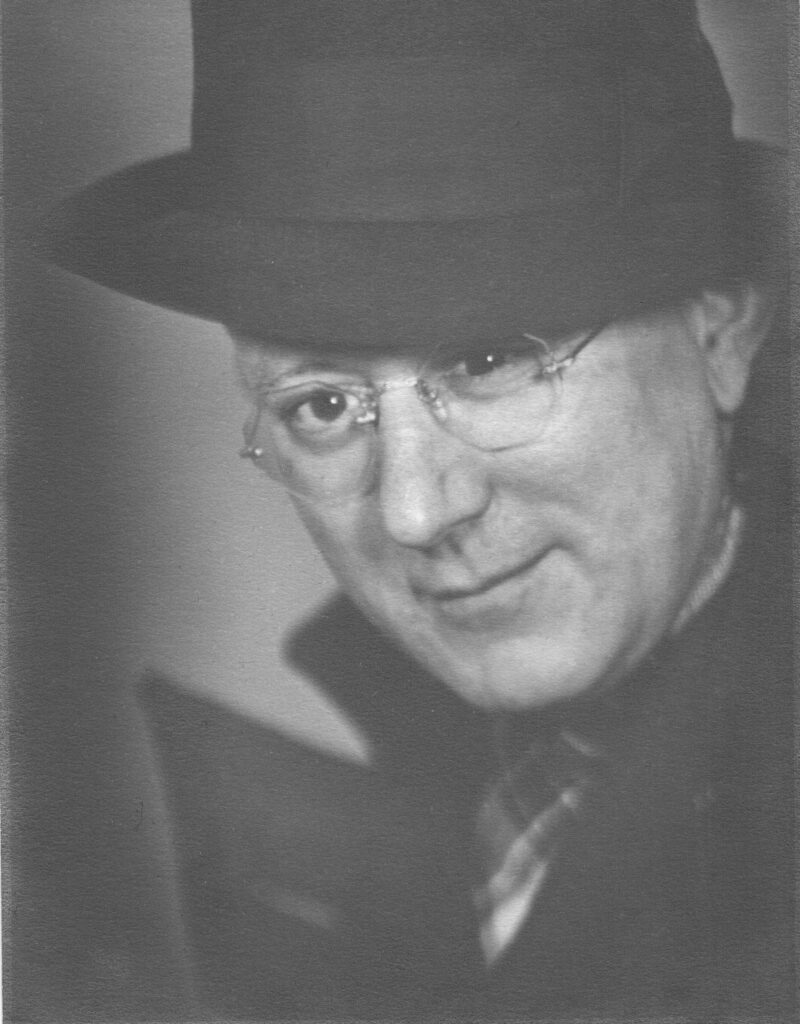

Manchester-born but with Romani roots (which he kept hidden) Hutchinson came from a nomadic people with a long history of experiencing persecution across Europe. This provided him with an understanding and sympathy for marginalized and deprived folks in his adopted Canada.

Although the man only lived in Hamilton from the early 1920s to the early 1940s, Hutchinson can be called a Hamilton artist.

In 1923, he left Tillsonburg in southwestern Ontario where his parents lived to attend night art classes at the Hamilton Technical Institute. He also did odd jobs, including dock work.

Hutchinson subsequently taught at the same school and began producing and exhibiting his art, which he continued throughout the 1930s.

In 1936, Leonard Hutchinson was appointed governor and curator at the Hamilton Municipal Art Gallery (today’s

Art Gallery of Hamilton). He belonged to arts organizations and was appointed to various prestigious positions, including associate of the Royal Canadian Academy.

Sometime during the 1940s, Hutchinson made a sudden move out of Hamilton (never to return) to Toronto, followed by taking up extended residence in his new country house near Thornhill.

The man dubbed the country’s best printmaker was no longer producing any art, including prints.

Instead, he took up work as a construction foreman.

Grace Inglis, who wrote an essay in book form accompanying a 1995 AGH exhibit of Hutchinson prints, suggested a reason might be that print-making was going out of fashion as the decade progressed.

Some might see this switch in careers by Hutchinson as a downward spiral in one’s life and even a personal failure. But that is not the case for Hutchinson as an English Romani, says his daughter Lynn Hutchinson Lee.

“He never lost sight of the social class he came from.”

In the 1970s, there was a renewed interest in Leonard Hutchinson at a time of cultural and political nationalism.

In that spirit, Lynn, under the name Lynn Hutchinson Brown, wrote the introduction for the 1975 NC Press book, Leonard Hutchinson, Peoples Artist: Ten Years of Struggle, 1930-1940.

There is a certain dichotomy in how Hutchinson functioned in Hamilton, writes Inglis.

In the late 1930s, he marched in solidarity with industrial workers seeking unionization alongside the likes of Sam Lawrence, the future pro-labour mayor.

He also hobnobbed with local Hamilton businessmen, teachers, and other elite figures who were the supporters of the arts in the city.

“My dad was not reserved. He was talkative, charming, flirtatious, eloquent, and enjoyed company,” says Lynn.

The back story is that early in his life Hutchinson had artistic ambitions.

To accomplish that, says Lynn, her father proceeded to “re-invent himself” as a middle-class Englishman without the social class or racial prejudices of the times getting in the way of a career.

“I think what happens is when you come from an ethnic group and you have negative experiences and there is a lot of hatred, you hide it, ” she says.

Lynn learned as a child that her father’s mother was Romani but paid little attention to her family origins until later as an adult when she fully embraced them.

Leonard Hutchinson was half-Romani. He was born in 1896 in Manchester to Lizzie Lee, a Romani servant. The father was her employer in Manchester, a doctor, and a non-Romani. The details are murky but it appears that Lizzie left that job and the doctor behind and paired up with a Romani man, Tony Hutchinson. The couple raised Leonard (now Leonard Hutchinson) and three other children.

Lynn never met either Lizzie or Tony. She did hear that Lizzie, her grandmother, was a striking figure with “flaming red hair, dyed with henna.”

In Europe, not all Romanies are constantly on the move in their caravans. In the case of Tony and Lizzie and their fellow English Romanies or Romanichals (as they are formally called) they were entertainers travelling from place to place. They made large puppets, each the size of a small child, for shows where young Leonard also played the violin.

“The Romanichals travelled or worked, trading or performing at fairs, as well as for seasonal agricultural work. A large feature of Romani travel throughout Europe was forced migration,” says Lynn.

Just a few years before the First World War started, Tony and Lizzie moved to the Tillsonburg area, joining one of Leonard’s sisters who had settled there earlier.

The couple and Leonard took up residence on one of the vast tobacco farms where they joined other migrants from Europe in the hard work of picking tobacco.

“They were pretty poor when they arrived. They were poverty-stricken,” says Lynn.

Leonard Hutchinson who was illiterate as a child (as was his mother) learned at some point how to read on his own.

Eventually, Tony and Lizzie earned enough money to buy a truck, which gave them the means to perform puppet shows on other local large tobacco farms.

The couple also bought land in the Tillsonburg area and built houses for themselves and Leonard’s sister.

At some point, Leonard went to England to serve in the British army in the First World War and later returned.

Grace Inglis at the AGH wrote that Leonard Hutchinson died in 1980 at the Our Lady of Mercy hospital in Thornhill after experiencing a series of strokes. His second wife Grace Fugler, originally one of Leonard’s art students in Hamilton and an accomplished print-maker in her own right, passed away a little over a decade later.

Fugler was the mother to Lynn Hutchinson Lee, a visual artist who has taken a literary turn. In 2022, she won the Joy Kogawa award for an excerpt from her unpublished novel Nightshade, which was inspired by her family’s experience in the tobacco fields.

Today, in Hamilton, courtesy of Lynn, you can view Leonard Hutchinson’s work on the Pipeline Trail just beyond the Main Street East and Ottawa Street North intersection. Among the murals permanently displayed on fencing or the side of garages are two Hutchinson woodcuts – Websters Falls and Builders of Roads.

This is just the kind of popular display of art that Leonard Hutchinson would have appreciated.

This article was originally published with Hamilton City Magazine.