With the news that Cadillac Fairview has sold Lime Ridge Mall after owning the Mountain mall for 42 years, it’s worth a trip into the history books to look at Hamilton’s first regional shopping centre.

Sometimes, I leave the lower city and head up the escarpment by public transit to Lime Ridge Mall, for which Primaris Real Estate Trust paid $416 million in June.

A Primaris press release says the Upper Wentworth shopping centre is a 793,000 square foot mall sitting on a 65-acre property. It is Hamilton’s largest mall.

I visit Lime Ridge because it provides greater choice in shops offering specific items such as men’s clothes and servicing for my cell phone than what is available in the other smaller malls in Hamilton closer to home.

The change of ownership is a big deal in Hamilton because Lime Ridge is visited by Hamiltonians across the city with a similar purpose in mind.

It is not clear what Primaris, which owns several malls across Canada, will do to improve the retail shoppers’ experience beyond filling up the enormous vacant anchor tenant space that was once filled by two department stores at opposite ends of the mall – Sears and more recently Hudson’s Bay.

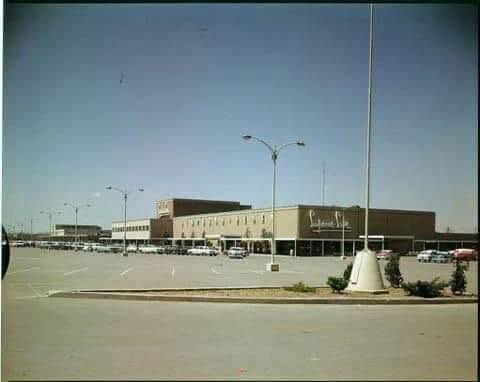

This kind of mass shopping venue has not always existed. The Greater Hamilton

Shopping Centre, which opened in the city a decade after World War II ended, revolutionized the retail experience for Hamiltonians.

An estimated 75,000 people (more than one-third of the population of Hamilton of a little over 200,000) showed up on the morning of Oct. 26, 1955 at the opening ceremony of the Greater Hamilton Shopping Centre in Hamilton’s east end.

Locally known simply as “the Centre,” it was hailed by The Hamilton Spectator in its extensive coverage as Canada’s first large regional shopping centre or mall. It remained the country’s largest mall for at least a decade.

Eager shoppers “jostled and stepped good-naturedly on each other’s toes,” while “jockeying” for a view of Mayor Lloyd Jackson formally cutting a red and white ribbon with silver shears.

A “carnival atmosphere” pervaded the Centre’s opening ceremony with people in the crowd wearing funny hats, waving flags and releasing balloons.

“A St. John’s Ambulance crew was on hand to handle any casualties in the stream of humanity that poured into the shopping area,” The Spectator story said.

Once the ribbon was cut, the shoppers queued up at the stores. Police were on hand to manage the traffic coming from Ottawa Street and Barton. Not all of the planned 60 outlets in the Centre were open yet, including the two new department stores, Simpson-Sears and the Montreal-based Morgan’s. But that failed to dampen the mood.

Shoppers had the option of hopping on a miniature train for 10 cents a ride to a particular store on the grounds. Merchants in the Centre offered trading tickets for the ride.

The Centre was situated on what was previously an almost 60-year-old Hamilton Jockey Club, a 71-acre race track in decline. It was purchased in 1952 for redevelopment by Toronto businessman E.P. Taylor, who saw an opportunity for a new shopping centre serving both Hamilton and the surrounding industrial Golden Horseshoe area.

The new shopping centre was targeting a post World War II generation ready to elbow its way into what the owners called “a new era of shopping.”

Hamilton already had small neighbourhood plazas of shops but nothing of this size and range of merchandise under one roof had been constructed or witnessed before here.

In offering, for the first time, one-stop shopping for the entire family for a range of household goods, food items and services as well as free parking, the Centre was built to bring back local customers who were leaving Hamilton to shop elsewhere, said Karl Fraser, president of the Greater Hamilton Shopping Centre at a press conference on Feb. 16, 1954.

“Between a quarter and a third of all the net effective buying power of all Hamilton is going outside the city. This is a huge market which we hope to attract for Hamilton through the shopping centre,” Fraser stated.

Other retail outlets in the new shopping centre included two large supermarkets (Dominion and Loblaws), banks, restaurants and a range of retailers selling clothes, household supplies and personal services such as barbers and beauty salons. There were also offices, car dealerships and a medical centre on the premises.

An additional treat for shoppers was a large farmers market on the parking lot north of the new shopping centre. At its height, somewhere in the range of 100 farmers would arrive to sell their in-season produce.

With the exception of the two-floor anchor department store outlets, the Centre was primarily a single storey arcade with canopied overhead walkways to allow customers to go from one end to the other without experiencing inclement weather. Certain portions remained open, much like a strip plaza.

The initial marketing in The Spectator was aimed at the entire traditional 1950s nuclear family of dad, mom, and the kids going on an excursion by car to the Centre.

The historical context of the 1950s helps to explain the immediate popularity of the new shopping centre in Hamilton.

One of the impacts of Canada gearing up its entire economy for its military effort during World War II was the enormous savings accumulated by many Canadians. There was so little to purchase in the stores because manufacturing was geared to producing necessary hardware for battle.

Those savings after the war helped to unleash a boom in a first-time purchase of homes, cars and home appliances by working-class families, explains John Weaver, a McMaster University historian and author of the 1982 book, Hamilton, An Illustrated History.

The development of the Greater Hamilton Shopping Centre was a byproduct of “the decentralization of retailing” flowing from the postwar construction of new communities of suburban tract homes, he wrote.

“The spread of retail activity reflected mass consumption of assorted conveniences and luxuries that now were within reach of most consumers,” Weaver noted.

Five years later, the glow had not come off. The Greater Hamilton Shopping Centre was still the largest shopping centre in Canada, according to a Nov. 12, 1960 article in The Spectator.

In its early days, the Centre’s customer base reached beyond Hamilton to southwest Ontario. Shoppers flocked from as far away as Kitchener, Galt, Guelph, St Catharines, Brantford and Niagara Falls. Keep in mind that Hamilton only had a population of 200,000 in 1960, but the same Spectator news story maintained that as many as 400,000 people came through the Centre’s doors on a weekly basis. That’s more than 20 million visits a year.

This regional shopping mall had 700,000 square feet of floor space, employed 3,000 people and generated sales exceeding $35 million in the latest fiscal year. Accounting for inflation, that is the equivalent of more than $375 million today.

So let’s compare those numbers to Lime Ridge, which generated $251 million in sales volume annually and 8.7 million yearly visitors, according to the latest fiscal numbers from Primaris.

Returning to the mid-1950s, the Centre also sponsored special events to attract customers of all ages, such as cooking demonstrations, a cow milking contest, car and boat shows, pet shows, the appearance of celebrities from popular television westerns and a stereotypical display of Indigenous culture featuring a teepee and an individual posing in regalia.

Fraser, the shopping centre president, also made assurances that neither downtown merchants or local east-end stores would lose business with the presence of the Centre.

Of course, in hindsight, we know that these promises could not be kept. Downtown Hamilton retail underwent a serious decline between the 1950s and the 1970s for various reasons, including the introduction of one-way streets and the tear-down of old streetscapes under city hall’s urban renewal policies.

Also, local regional shopping centres tend to out-compete local merchants on both convenience and price. This is exactly what happened to south-east Hamilton, with the exception of Ottawa Street North, which remained a vital destination location for fabric and specialized independent shops.

Over time, shopping at the large malls became the norm in many urban centres. The shopping centres were adding stores and undergoing continuous renovation and change. What was originally the Greater Hamilton Shopping Centre reopened as the much-changed Centre Mall in 1974.

It was now a completely indoor shopping centre of which there were countless and comparable examples across North America built by large developers. The concept was based on a finely tuned model developed in the U.S. by Austrian-born architect Victor Gruen. Typically, indoor malls were set up under the roof of a large building complex that contained a climate-controlled shopping environment replete with atriums, gardens, escalators and food courts. Gruen’s first designed indoor mall, the Southdale Mall in Edina, Minnesota opened in 1956, just one year after Hamilton’s Centre drew its 75,000 visitors.

There were other upgrades at the Centre Mall. In January 1983, 44 new stores were added, including a new K-Mart department store and the Mall Cinemas were renovated and expanded, becoming the largest cinemas in Canada with 2,400 seats in eight theatres.

But financial difficulties were already looming, especially as the scaling down and closing of industrial plants began in the 1970s. Then came competition from Eastgate Mall in Stoney Creek, which opened in April 1973, and later Lime Ridge, which opened on the Mountain in 1981.

In the early 2000s, stores and other mall amenities, such as the movie theatres, closed at Centre Mall.

Centre Mall continued to host events and celebrations to reinforce its east Hamilton ties. One example of this happened at the end of October 2005 when residents were invited by the management of Centre Mall to attend a two-day event marking the original Greater Hamilton Shopping Centre.

“Centre Mall: Celebrating 50 years in the community,” read the headline in the advertising announcing the event in The Spectator.

“This mall has grown alongside the residents of this community and many who shop here today remember shopping here 50 years ago,” stated marketing manager Margaret Dickson in the same ad.

Plans were in the works to bring the Centre and its more than 100 stores into the 21st century, but no specifics were provided.

One year later, the news came from the two corporate owners, CPP Investment Board and Osmington, that the Centre Mall would undergo an extensive $100-million “rebirth.” In 2007, it was announced that the mall would be torn down.

Today, what is now officially the Centre on Barton contains a series of free-standing big-box stores or so-called “power centres,” including Canadian Tire, Walmart, Michaels and Staples that are best accessed by automobile. With a large parking lot and pedestrian walkways that don’t lead anywhere, Centre on Barton is not designed for walking or cycling. The backs of the outlets face Barton Street and thus have no relationship with the surrounding area. And there are no longer special community events on the site.

In addition, the much-celebrated 52-year-old farmers market at Centre Mall was moved as part of the conversion to the power centres, despite the unanimous opposition by Hamilton city council. It has since relocated to Ottawa Street North but on a diminished scale.

Yvette Cowe, a cheese store owner on Ottawa Street North, has fond memories of Centre Mall before it was demolished.

“We had a family restaurant in the front entrance that everybody loved. The food was good and inexpensive. You could go there and have a good lunch, and then you go to Zellers to buy diapers.”

Cowe was a young mother frequently visiting Centre Mall in its last years. “It was safer than it is now. You could actually walk there with a stroller with small children,” she said.

She echoes what I have heard from others living in east Hamilton. Even as a dying mall, Centre Mall continued to attract mothers with their kids, seniors and teenagers. Local people clung to what was left of a once major shopping centre. There was then – and it continues today – no other community space in the immediate neighbourhood of Barton between Ottawa and Kenilworth where one can just gather and hang out with other residents.

The community atmosphere at Centre Mall would have delighted Victor Gruen. A socialist, he became so disillusioned by what he saw as the soulless and consumerist nature of large corporate malls across North America that he returned to his native Vienna in 1968. There, he discovered Shopping City Süd (now one of Europe’s largest malls) was being built in the countryside just outside his home town.

Kate Black, a self-professed mall rat from Edmonton, offers these anecdotes about Gruen in her 2024 book Big Mall: Shopping for Meaning as an example of how history and social bonds are erased in what one anthropologist calls “non-places.”

In the wake of its purchase of Lime Ridge Mall, the only thing that Primaris has revealed about its plans is real estate development on the property in partnership with another company. Perhaps, the new owner should take a lesson from the experience of both the Greater Hamilton Shopping Centre and later Centre Mall, which is the value of combining shopping (which we all have to do at some point) and enhancing a sense of community on the mall property. Maybe Lime Ridge should start sponsoring community events for the Mountain, including children’s events, music concerts, theatre productions, festivals and art shows. Something has to be done to make the mall fun again.

The original version of this article appeared in Hamilton City Magazine, Fall 2025 edition.